Irish Women Artists: Mary Swanzy

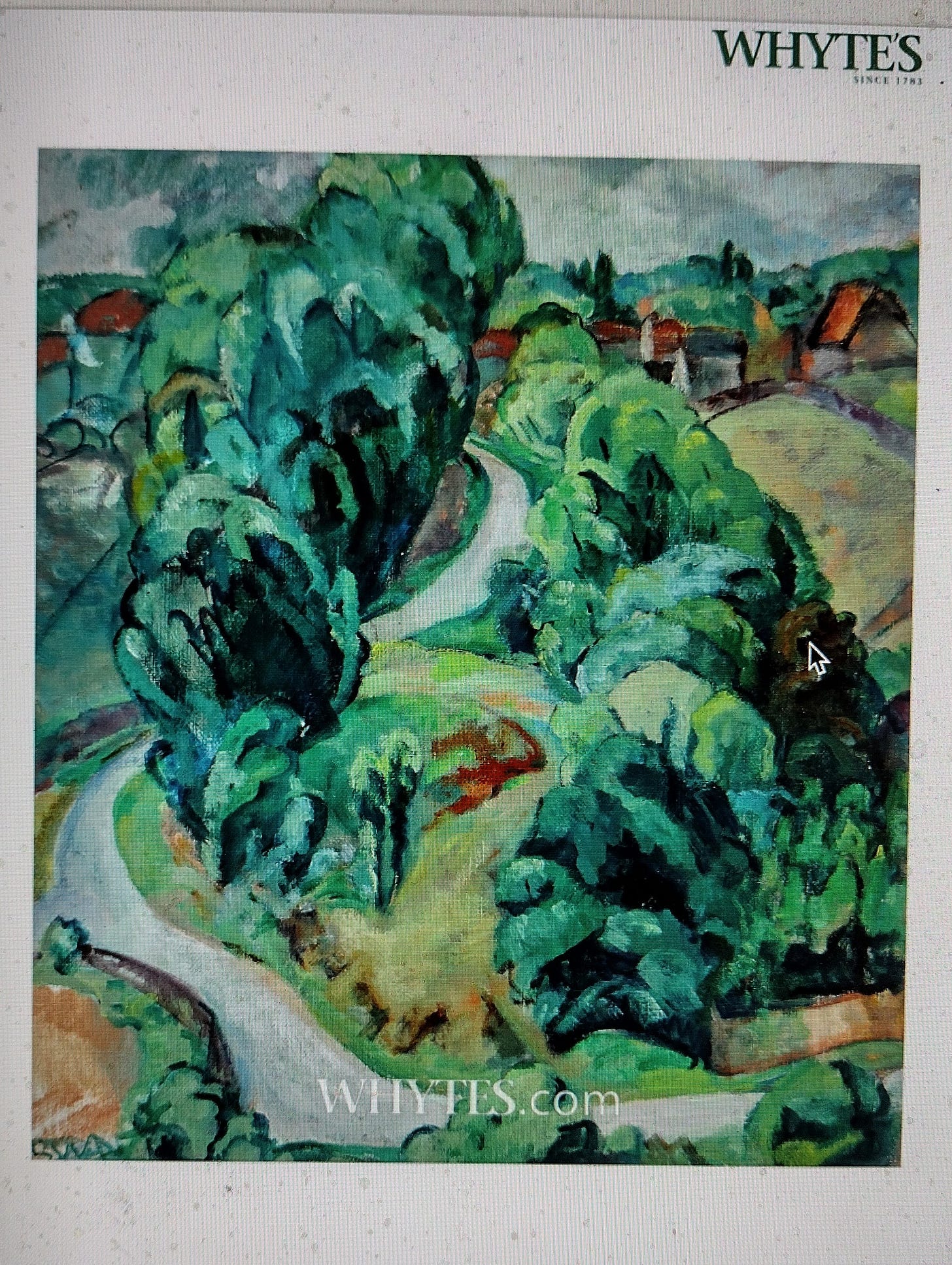

'La Route', a painting by Mary Swanzy was for sale by Whytes on Monday 3 March 2025 with a guide price of €20,000-30,000. It sold for €36,000.

Mary Swanzy: individualist supreme

In 1932, Sarah Purser, always a supporter of young Irish artists, held an exhibition of Mary Swanzy’s work for invited guests in her home at Mespil House. Purser had spotted Swanzy’s artistic talent early on, advising her to go to Paris for training and later on, in 1913, reviewing her first show at Mill’s Hall, Merrion Row.

Over a lifetime even longer than her mentor’s – Swanzy died at the age of ninety-six, Purser at ninety-five – Swanzy remained consumed by her passion for painting. She would become the most eclectic and versatile of Irish artists, embracing Cubism, Futurism, Fauvism, surrealism and her own unique version of whimsical animism. Her art was her life and her life was her art.

Yet Swanzy was no mad genius. Her upbringing was absolutely conventional for a woman of her class and time. She was born in Dublin on 15 February 1882, the second of three daughters; St Clair was the oldest and Muriel the youngest. Two other children, both sons, died in infancy. Her father, Sir Henry Rosborough Swanzy, was an ophthalmic surgeon who played a central role in establishing the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital in Dublin. Her mother was Mary Denham, daughter of John Denham, a doctor who had served as president of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. The family lived in a rented house at 23 Merrion Square North, an area of Dublin City then occupied mainly by members of the Protestant professional classes.

Swanzy was a delicate infant, thought unlikely to survive, but by the 1890s was a student at Alexandra College on Earlsfort Terrace, a short walk from her home. Although it was strict, she described her childhood as ‘a gift from heaven’. Her mother, a Presbyterian, would regularly read to her children from the King James version of the Bible. She would also become well versed in Celtic, Egyptian, Buddhist and Hindu spiritual traditions, which fed into her art.

Determined to learn how to draw, Swanzy became a regular at the art classes of Josephine Webb at Lower Pembroke Street after first attending a Saturday watercolour class with Miss Underwood at Herbert Place. She retained a great love for Dublin all her life: ‘I had the great privilege of growing up in a completely Georgian city. Everything was in proportion, the size of the squares related to the width of the streets…. It was one of the most beautiful cities in the world.’ Living close to the National Gallery of Ireland, Swanzy spent hours studying and copying the great masters, encouraged by its director Walter Armstrong.

Around the age of fifteen, Swanzy was sent to a boarding school in Versailles, France, and later to a day school in Freiburg, Germany, becoming independent of mind and fluent in French and German. In Dublin, she took further art classes with May Manning, who recommended that she attend evening lessons on modelling with the sculptor John Hughes at the Metropolitan School of Art.

In the summer of 1898, when John Butler Yeats was teaching at Manning’s studio at Ely Place, Swanzy met Yeats’s friend, the artist Clare Marsh, who was supporting herself though painting and teaching. Through Marsh, Swanzy became acquainted with the Yeats family at a time when John’s son Jack was breaking through as an experimental artist and his older son, the poet William, was a leading light of the Celtic revival.

By 1901, Swanzy was showing her work at the Young Irish Artists Exhibition at Leinster Hall in Dublin and winning the first of three Taylor Art Scholarships for a work called Study of a Girl’s Head. Swanzy’s Royal Hibernian Academy debut at the annual exhibition of 1905 included a work called Portrait of a Child; she would continue to exhibit portraits every year until 1910. Among these were commissioned portraits of Mrs Pollock, Reverend David Purvis and W. Kingsley Tarpey. Family members also posed for her, including her sisters early on and later, her brother-in-law James Tullo and her niece Mary St Clair Tullo.

Encouraged by both May Manning and Sarah Purser, Swanzy went to Paris in 1905, working at the Delacluse studio in Montparnasse, where Lucien Simon was one of the teachers. Simon was best known for his realistic paintings of working people in Brittany. ‘I had to go there where the teachers would know how to teach, which was by not teaching you at all…you did your work and you saw what they were doing around you and your fellow students criticised you and you criticised them…and once a week the master came round and told you how bad your work was…until you learned to do better.’

Mary Swanzy worked hard, arriving at the studio by 7.45am. She would draw and paint from life all day with only a short break for lunch, then a sketch class in the evenings and bed by 8pm. It left little time for the bohemian lifestyle: ‘You did not sit up at night carousing and drinking and making a fool of yourself. I couldn’t afford to. I couldn’t afford to be idle.’ On Sundays, when entry was free, she would go to the Louvre to study and ‘copy’ the masterpieces of the collection.

‘To be an artist… you have to be very severe with your amount of energy…. To have an overriding hobby, that’s the secret. Mine was an overriding hobby, I couldn’t get rid of it.’ To the end of her days, she would maintain, with scarcely believable diffidence, that her art, the art that obsessed her, was a ‘hobby’.

After a few months back in Dublin, Swanzy paid a return visit to Paris in 1906, moving on to the studio of Antonio de La Gándara, and also taking classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Colarossi, which was one of the few studios then allowing women to paint from the male model.

It was either through Sarah Purser, who knew Stein, or de La Gándara, part of the Parisian gay sub-culture, that she met Gertrude Stein, an important patron of modern artists in Paris. Like few other Irish artists, she found herself exposed to modernist art at its most innovative. She would later remember how normal it was to rub shoulders with emerging painters, such as Picasso, but also with Gauguin and Matisse: ‘The names that are known now were not known then …. When I arrived as a student in Paris, Picasso was a young man trying to make his way but he wasn’t known. Gertrude Stein used to have a kind of a soirée and you could go to her house and see all the Picassos there. That’s how we got to know about him. He was a little man who painted.’

By 1905, artists like André Derain and Henri Matisse were revolutionising art with their emphasis on pure colour and Primitivism. They were dubbed ‘les Fauves’ by the critics, which was French for ‘the wild beasts’. Swanzy watched and learned. Like Pablo Picasso, she would adapt and experiment with the latest artistic trends all her long life, making them her own. As Picasso himself said, ‘good artists copy, great artists steal’. She refused to compare artists. ‘I don’t like comparisons. I recognise those who are true painters and those who are not. I recognise those with honesty and probity in their work.’

In 1906, Swanzy won another Taylor Art Scholarship and exhibited two paintings at the RHA, where her portrait of her father showed her mastery of the academic skills. Nathaniel Hone called it ‘the best picture painted in Dublin in the last thirty years’. Her 1907 portrait of her sister Muriel was more reflective of modern trends, showing the influence of Fauvism, with the background painted in a series of interlocking lines, but also of the Pointillists who painted dots of pure colours that blended in the eye of the beholder.

From 1908, Swanzy shared a studio with Clare Marsh at the North British and Mercantile Building on Nassau Street. From there, she fulfilled several commissions for portraits and attempted commercial illustration, including an advertisement for Savoy Chocolates. ‘My father thought I should follow in the steps of Miss Sarah Purser, but I wasn’t able. I opened a little studio of my own and tried to teach for a while. But I didn’t like it. You can’t teach painting, you can only learn by doing it,’ she would say in a 1974 interview with Una Lehane of the Irish Times. Both Swanzy and Marsh supported the suffrage movement, along with their friend Mabel O’Brien Purser, a niece of Sarah’s, who ended up jailed for a month in 1913 after a protest when windows of the Custom House in Dublin were broken.

Swanzy’s mother died in 1909 and by 1910, her younger sister Muriel had married James Tullo, a chemist who worked with Arthur Guinness and Company. Swanzy was exhibiting regularly, getting occasional mentions in the press and still attending the Metropolitan School of Art. In March 1913, while Swanzy was in Italy, her father died and the lease on the family home ended, with the contents of the house auctioned. It left Swanzy both grieving and homeless at the age of thirty-one. Her inheritance of just over £4,000 gave her some independence, but she would need to keep selling her work in order to survive. All her life she remained frugal, reluctant to turn on the heating and eating the plainest of food, as Wilhelmina Geddes would comment in later years after visits to Swanzy’s home in London.

Later that year, Swanzy held her first one-woman exhibition at Mill’s Hall, Merrion Row, showing eighty paintings. Sarah Purser was impressed. ‘I wish I could paint like Miss Swanzy,’ she commented to Thomas MacGreevy. In 1914, she exhibited with the Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris for the first time, where Orphism, an offshoot of Cubism influenced by Fauvism and practised by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, was a dominating trend. Another influence she absorbed was Futurism, a movement founded in 1909 by Filippo Marinetti. Many of Swanzy’s Cubist-inspired works of the late 1920s and 1930s reveal her keen understanding of the Futurist aesthetic which sought to transmit the energy of the modern age through images of flight and of the city. That year, she travelled to Italy, taking a studio in Florence. Because the cost of living was cheaper in Italy than in Ireland, she intended settling there for a few years.

The outbreak of World War I forced a return to Dublin and Swanzy exhibited both at the Grosvenor Gallery in London for the first time and at the Salon des Indépendants of 1916, despite the drama of the Easter Rising. She had been in Dublin at the time and remembered the looting, but little else. Unsettled by the uneasy atmosphere in Ireland, she left Dublin for Paris in October, basing herself for five months at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, which had the great attraction of providing studio facilities at a low cost. It was here that Swanzy began experimenting with Cubism.

By the spring of 1917, she was back in Dublin, living in digs and, from October, attending the Metropolitan School of Art. Around that time, on the eve of the October Revolution, her sister St Clair had a narrow escape from Russia where she had been teaching English to the Tsar’s extended family. After she returned to Dublin, St Clair worked as a recruiting controller for the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps; when Mary applied to join, she failed the medical test. In an eventful year for the sisters, Muriel gave birth to her first son, Henry, that year. A second son called Francis was born in 1918 and a daughter, Mary St Clair, in 1923.

In the spring of 1919, Swanzy held a second one-woman show of fifty-four paintings; her Dublin address was given as 9 Garville Avenue in Rathgar. In her review, Sarah Purser noted the lack of melancholy and the light optimism of Swanzy’s Irish landscapes. Also that year, Swanzy made her debut at the Paris Salon, showing her Cézanne-influenced Tulips. She had visited the area around Mont St Victoire near Aix-en-Provence, making a number of small paintings of the view immortalised by Cézanne. Her second picture at the Salon, La Poupée Japonaise, or Young Woman with Flowers, showed an awareness of Cubist principles, with the removal of perspective and shifting planes. Swanzy retained an element of narrative, with the face of a girl and a bouquet of flowers floating over the geometric shapes. She was clearly aware of the work of Lhote and Gleizes, the Cubist teachers of Jellett and Hone, and explored Gleizes’ theories of translation and rotation in her notebooks as she developed her own interpretation of Cubism. Whether she was the ‘first’ Irish Cubist is open to question, since she was notoriously lax in naming and dating her work. However, she would have become acquainted with Picasso’s early Cubist works at Gertrude Stein’s apartment and had possibly visited the Salon des Indépendants exhibition of 1911, where abstract Cubist art was presented to the public for the first time.

In Dublin, she shared another studio with Clare Marsh, this time at 31 South Anne Street, where Marsh conducted popular art classes. In 1920, Swanzy and Marsh were founder member of the Dublin Painters Society, spearheaded by Paul Henry and his then wife Grace Henry. While in Paris, she would join the committee of the Société des Artistes Indépendants after it resumed its work post-war, showing three paintings in 1920. During that year, she made an extended visit to St Tropez, a popular destination for artists, where Paul Signac, the president of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, was based. Among the works inspired by this visit was a Cubist-influenced painting called Sunset on Sails in St Tropez, which captured a strong sense of movement.

While World War I may have ended, Ireland remained in turmoil, with the War of Independence raging. In March 1920, Swanzy’s second cousin Oswald Swanzy, a district inspector of the RIC, was implicated in the murder of Thomas Mac Curtain, Lord Mayor of Cork. Although he was transferred for his own safety to Lisburn, he was tracked down by Michael Collins’s intelligence network and shot dead on 22 August. His death triggered a wave of loyalist riots and sectarian violence in which more than thirty people died. With the family name long linked to the Anglo-Irish establishment, it was not a comfortable time for the wider Swanzy family.

By now, Swanzy’s sister St Clair was involved with Lady Muriel Paget’s mobile relief missions in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia and, in November, Swanzy left Dublin to join her. Over the next few months, the sisters visited Bratislava, Prague, Dubrovnik and Belarus, as well as Ragusa in Sicily, all places ravaged by famine. When she was not helping out, Swanzy painted landscapes and scenes of village life, which were shown in the autumn of 1921 at the Dublin Painters’ Gallery, along with work by six other artists, among them Jack B. Yeats and Paul Henry. In December of that year, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed and British rule over Ireland ended.

In Paris, Swanzy’s work was included at the Exposition d’Art Irlandais, held to coincide with the Irish conference in Paris from 28 January to 25 February 1922. She returned to eastern Europe that spring, with her sketches depicting local life – markets, traditional public events, the mountainous landscape – later worked up into Fauvist-style paintings. After she returned home, she held a one-woman show of her Czechoslovakian drawings and paintings at the Dublin Painters Gallery in June, as well as exhibiting at the Salon des Indépendants.

In 1923, Swanzy showed works at the first exhibition of the New Irish Salon at Mill’s Hall and in London at the Society of Women Artists, as well as at the Salon des Indépendants and the Beaux Arts. In May came the sudden death from appendicitis of Clare Marsh, aged forty-seven, which shocked Swanzy deeply.

By then she was organising an ambitious journey to Hawaii via Quebec and the United States. Always restless and seeking new inspiration for her work, she may have been influenced by the French artist Paul Gauguin, who famously spent many years in the South Sea islands, first in Tahiti, and later the Marquesas Islands. There was also a family connection. Her uncle, Francis Swanzy, had emigrated to Hawaii from Ireland in 1880 where he became managing director of a sugar business. He had died in 1917, so Swanzy would be the guest of his widow Julie, who lived in some comfort at a large house called La Maison Blanche in Manoa, Honolulu. Swanzy arrived in Hawaii on the SS Montcalm on 8 September 1923 and would not return to Ireland for fifteen months.

The setting proved as stimulating as she had hoped. She wrote to Purser of the ‘perfect climate and beauty … I feel a draw towards tropical scenes’. In February 1924, she showed some of her paintings at a private exhibition in her aunt’s house. In May and June of that year, she visited Samoa, a journey that took seven days of sailing, motivated by ‘everlasting curiosity’. Staying with a local doctor in far more primitive conditions than she had experienced in Hawaii, and overwhelmed by the visual richness, she painted local flowers, trees and native women, reverting to a more naturalistic style and making dozens of quick sketches illustrating the everyday life of the people.

After returning to Hawaii, she showed her Samoan paintings at the Cross Roads Studio in Honolulu. In September, she sailed for Los Angeles, staying for a time in Santa Barbara, California, where she worked in a local studio and exhibited some of the Samoan works at the Santa Barbara Arts Club Gallery. After visiting New York, she returned to Ireland in February 1925, staying with her sister Muriel and family in Coolock. She exhibited three of her Samoan paintings at the RHA exhibition, while her one-woman show in October 1925 at the Galerie Bernheim Jeune in Paris, where Purser’s old friend Félix Fénéon was director, included fourteen Samoan canvases. Gertrude Stein wrote her a note of congratulation.

In 1926, Swanzy exhibited both at the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon itself in Paris. By the end of the year, she was living with her sister St Clair in a rented house on Kidbrooke Road in Blackheath, London, where the sisters had a flat each. ‘We had two flats in the same house, where we lived in separate amity,’ she would say. She managed to travel ‘by saving’ and by renting out her flat: ‘because our house was near Woolwich and the National Nautical College, there were always people who needed to rent a flat in the area for short periods. I let my flat and went off on my travels.’ Swanzy admitted that while she loved Ireland deeply, she couldn’t stand ‘the narrowness’ of Irish life. The newly independent nation was increasingly small-minded and introverted, not welcoming to artists, or indeed to outside influences of any sort. Film and literature had faced increasing censorship following the establishment of the Committee of Enquiry on Evil Literature in 1926, which was heavily influenced by the Catholic hierarchy. As well as Swanzy, artists such as Leech, Orpen, Hughes and Geddes left the country, as did the writers Samuel Beckett and Seán O’Casey. James Joyce had left in 1909.

Swanzy’s work appeared regularly at exhibitions in Dublin and London over the next few years and although the Wall Street Crash had created global uncertainly, she continued her travels. In a letter to Wilhelmina Geddes from San Gimignano in Tuscany, she wrote that while she was happy to be there she intended to try somewhere else. Most of her works at the time were Cubist landscapes and cityscapes. In 1929, two of her paintings were shown at The Women’s International Art Club, while five of her works were included in the Exposition d’Art Irlandais, held in Brussels in 1930.

In Dublin, Purser continued to support her young protégée and among the invited guests to the Mespil House exhibition of Swanzy’s work in February 1932 were Mainie Jellett and May Guinness, both of them admired by Swanzy. The governor general of the Irish Free State, James McNeill, also attended.

Mary Swanzy remained faithful to the Salon des Indépendants showing two landscapes in 1932, two more at the fiftieth anniversary Salon in 1934 and other works between the years 1936 and 1939. In September 1932, she held a solo show of twenty paintings at the Reid and Lefevre gallery in London. The Times gave a succinct description of her art at this time: ‘Miss Swanzy may be described as a Surrealist working in a Cubist convention … the majority of her works look as if they were an illustration of a disordered dream.’ Swanzy, typically, was adapting elements of surrealism and using them to her own ends. Unlike her, many female artists had distanced themselves from surrealism because of its clear misogyny or, like Leonora Carrington, because the public was not prepared to accept a woman’s work in that genre.

Swanzy continued her routine of painting and exhibiting over the next few years, with regular visits to Dublin and elsewhere from her London base. She preferred to sell from her home rather than deal with an agent or a gallery and did not send paintings to the RHA for about ten years after her move to London.

In 1936, an unexpected inheritance allowed Swanzy to buy a house at 45 Hervey Road, Blackheath, London. Wilhelmina Geddes was a regular visitor at holiday time and travelled with Swanzy on at least one trip abroad. In 1937, after an absence of twelve years, Swanzy was a surprise exhibitor at the RHA show with a portrait of Mrs Thomas Smalley. In London, her work was included in a Dublin Painters exhibition held at the office of the High Commissioner in 1938.

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, Swanzy visited Paris; an event that would have a significant effect on her work. In London, she experienced the Blitz and the horrors of war at first hand. Soon after, the Swanzy sisters were evacuated to Radnorshire in Wales. While they were there, St Clair’s home was bombed and destroyed.

Swanzy’s Ebb Tide, also called Crouching Figure with Bowed Head and graphically illustrating her despair at the outbreak of war, dates from 1941; it is considered a self-portrait. She retreated to Ireland in 1942, living with her sister Muriel and family in their Coolock home for three years. During this time, she exhibited with the Dublin Painters’ Society in group shows and also as an individual artist. In 1945, her work was shown at the annual RHA exhibition. Because of Ireland’s neutral status, Dublin had become a hub of artistic endeavour, with Irish artists such as Louis le Brocquy and Patrick Hennessy returning from their European bases and joining the British artists sitting out the war years in the relative calm of Ireland.

Swanzy’s works of the time have a darker edge, with several works called simply War. A nephew was conscripted, and her portrait of her sister Muriel shows her staring anxiously out a window, presumably awaiting the return of her son. Swanzy’s work from this period has proved a valuable and unflinching record of the horrors faced by ordinary people in war. As she put it herself, her paintings are far from the pretty pictures of ‘pussy-woosies and doggie-woggies’ expected from female artists of that era. In 1943, she showed five paintings at the inaugural Irish Exhibition of Living Art. It was a period of mixed emotions. Her mentor Sarah Purser had died only a month earlier, while Mainie Jellett was too ill to attend.

In March 1944, she held a one-woman show at the Dublin Painters’ Gallery, which was widely praised. The work she was producing was diverse, both in subject matter and style. She decried the vulgarisation of life, and paintings such as Figures Drinking, Intelligent Folk, Taxi, The Wedding and many more echo the work of Goya, Hogarth and George Grosz in satirising the wealthy.

In that same year, Swanzy’s portrait of Sarah Purser was presented to the Municipal Gallery by the Friends of the National Collections Ireland, while her haunting anti-war painting The Message was given to the Gallery by the Haverty Trust. She returned to London shortly before World War II ended, with St Clair joining her at Hervey Road. In 1946, Swanzy exhibited at the St George’s Gallery, London, along with Henry Moore, Marc Chagall and William Scott. A solo exhibition of thirty-four recent paintings followed at the same gallery in the spring of 1947, the last exhibition of her work in London during her lifetime. During the summer, she travelled to France and Switzerland. Geddes continued to visit, especially during the holiday periods, with her diary noting their shared belief in the importance of drawing and ‘a feeling for the Classical ideal’.

In 1949, Ireland became a republic and Swanzy was made an honorary member of the RHA, showing with them in 1950 and 1951; she was now aged sixty-nine. She continued to travel to France, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Italy in those years, and although she did not exhibit any work between 1953 and 1968, she never stopped painting. Her work from those years was increasingly surreal and allegorical, combining recognisable human beings and animals of many kinds, and fantastical creatures which blended the two. Hieronymus Bosch is one likely reference, along with post-War Leonora Carrington, whose work featured hybrid bird/humans. Geddes died in 1955 and Swanzy’s sister St Clair in 1967, leaving her alone and increasingly reclusive. ‘I find when I get absorbed in a painting, I forgot all about putting on the potatoes. I have nobody living with me. I couldn’t stand it – and they wouldn’t be able to stand it either. But I have good helpers who are very devoted and very kind.’

Her regular visitors included Dr Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, a member of the Purser family, who was organising a retrospective of her work, and the young art critic Hilary Pyle. She also had the support of her neighbours, Hugh and Colette Hawes, art lovers who took special care of her, especially after a fall when she broke a hip. Following the major retrospective of her work at the Dublin Municipal Gallery in 1968, which received widespread publicity and stimulated renewed interest in her work, Swanzy held solo shows at Dublin’s Dawson Gallery in 1974 and 1976. In 1975, her work was featured at the Cork ROSC and she resumed showing with the RHA. She continued to paint, taping up her arthritic hands so she could hold a brush, until her death at her home in London on 7 July 1978 after a fall. She was ninety-six. A painting called The Three Ages of Woman was on her easel at her time of death.

In an Irish Times article of 1968, Swanzy was quoted as saying: ‘I think myself that the only means I have ever had of knowing anything has been through painting. Anything I have known of life is there. I am an extraordinarily lucky person – I have had an absorbing passion – painting.’