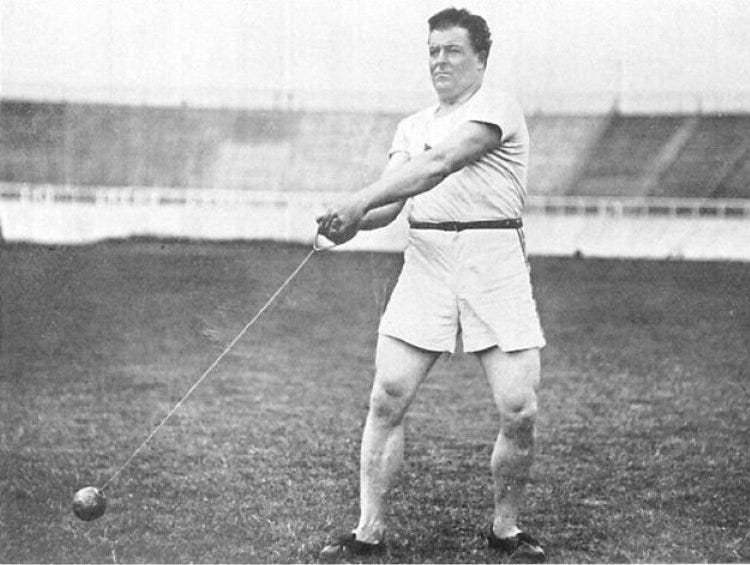

At the prize-giving ceremony for the St Louis Olympic Games, held in 1904, John Flanagan, from the Kilmallock area of Co Limerick, became one of the first athletes to receive a solid gold Olympic medal for his victory in the hammer. The practice was quickly discontinued, with gold plate replacing pure gold after 1912.

In St Louis, Flanagan was winning his second Olympic hammer title. Although not included in the programme of the first “Olympian” games of 1896 in Athens, hammer throwing had become part of the schedule when, in 1900, the second such games were held in Paris.

Hammer throwing had a long history; it was mentioned in the romances of the Middle Ages and legend has it that no less than Henry VIII excelled at throwing the ‘sledge hammer’. Around 1550, a young woman called Betty Welch regularly beat all the men in sledge hammer throwing. In Ireland, hammer throwing in various forms can be traced back to the Tailteann Games of 1829 BC.

By the late nineteenth century, Irish throwers were setting the pace for the discipline as the rules evolved rapidly. Rather than taking off at a run before releasing the implement, the accepted — and less hair-raising — means of launching the hammer became rotating in a circle nine foot in diameter; later reduced to seven foot. On the 7.2kg hammer itself, the wooden handle was replaced by piano wire.

With competition becoming more regularised, the first of many Irish throws giants to impress was William Barry, followed soon after by James Mitchel. Next was Flanagan, who is widely considered the father of modern hammer throwing because of his life-long commitment to improving technique. Only in his thirties would he perfect the three-spin pivoting style he had first seen executed by the American Alfred Plaw.

His first ‘world record’ came in Clonmel on 9 September 1895, when he threw 44.46m, breaking Mitchel’s best effort of 44.19m set in 1892. However, since implements and styles varied greatly, world records in the hammer were not recognised by the international athletics body until 1913.

Some forty-two years later in 1937, at Fermoy, Flanagan would witness his protégée Pat O’Callaghan unofficially breaking the world record with a throw of 59.54m — well over a metre further than the first official world record of 57.77m set by his old friend Paddy Ryan in 1913. Because of the complicated politics of Irish athletics, this record was not ratified.

John Joseph Flanagan was born on 28 January 1868 and grew up in the town-land of Kilbreedy East, near Kilmallock in County Limerick, Ireland. He was one of seven sons and a daughter. His father Michael, a champion weight thrower in his time, was a farmer. His mother Ellen Kinkead had strong connections with the USA.

A short but powerfully built man, Flanagan, who had played hurling for Munster, began his athletics career as a sprinter and jumper; at the age of twenty, he jumped 6.70m in the long jump and 14.04m for the triple jump; in 1893, he won a Munster title in the 56lbs, which was his first notable throws win. He was in the great Irish tradition of all-rounders; a tradition encouraged by the system of handicapping, which meant athletes tended to avoid their best events where they would have had no chance of winning a prize.

Not until 1895, at the age of twenty-seven, did he decide to concentrate on the throws, studying the hammer technique of Maurice Davin and Tom Kiely and evolving his own two-spin technique. A year later, in 1896, just a week before Athens ‘Olympian’ Games, opened, Flanagan was competing a GAA-organised festival of Irish sport at Stamford Bridge. At the meet, Flanagan broke not only his own hammer world record but also set a world record for throwing the hammer from a old-style nine foot circle. Both Flanagan and Kiely played for a Munster hurling team that beat Leinster at the festival. On 4 July, Flanagan also won the British AAA title using the old-fashioned hammer with cane handle. He threw of 40.22m.

Later that year, he was persuaded by his uncle Eugene Kinkead, a former US congressman, to emigrate to the USA. After joining the New York Athletics Club, he began setting records in a range of throwing events. He would switch to the Irish American Athletics Club in 1905.

Technically, the hammer had progressed since a wire handle and the seven foot circle had become standard. Ever the innovator, Flanagan was responsible for introducing ball bearing swivels and a double grip to the implement.

His first US competition was at a Knickerbocker club match in Bayonne, New Jersey on 31 May 1897 where his 45.94m effort saw him become the first man to throw a hammer more than 150 feet (45.72m). Soon after, he won the first of his seven American hammer titles and the first of six 56 lb titles.

He was thought without rival until news filtered through in 1899 that Tom Kiely had thrown 49.38m. Six weeks later, on 22 July 1899, in Boston, Flanagan responded with a mighty throw of 50.01m, making him the first man to throw further than fifty metres.

From 1898 to 1908, Flanagan was the biggest draw in North American athletics, topping the bill at meets all over the USA and Canada. Adding to the spice were his many battles with McGrath and later Con Walsh. Like many other Irish emigrants, Flanagan had joined the New York police force in December 1902, taking five years off his age to ensure his acceptance. A few months later, he married Mary Lillis, from Kilmihill, in Co Clare, with the couple settling in the Bronx. They had one child, a boy, who died in infancy.

His peak years were 1904 and 1905 when he collected titles for the hammer and the 56lb at championships in the USA and Canada as well as at a Tailteann Games organised in New York. In 1905, Flanagan competed in the Police Athletic Association Games at Celtic Park in New York. ‘Not only did he win four of weight-throwing events, but, as if to show that he could do a little sprinting as readily as he can outclass his competitors with the 16 and 56 pound weights, he not only had the temerity to enter the fat men’s race, but actually won it.’

His first of three Olympic titles came in Paris 1900. With the American team, Flanagan warmed up for Paris by competing at the AAA Championships at Stamford Bridge on 7 July, which at that time, was the world’s most prestigious athletics meeting. Flanagan duly won the hammer, stretching his own championship record to 49.78m.

In Paris, Flanagan was trailing Truxton Hare, an ex-American footballer, who threw 49.13m in the early rounds. He pulled out a final 51.02m effort for victory. Four years later, in St Louis, Flanagan won by less than a metre with an Olympic record throw of 51.23m. He also finished second ahead of James Mitchel in a closely-fought 56lb weight throw, with a best of 10.16m. In the discus, won by Martin Sheridan, he finished fourth.

Four years later, in London, Matt McGrath was favourite to win the event following a 52.91m throw a year earlier. Despite an injured leg, McGrath threw 51.18m. and as in 1900, it came down to the final round. Flanagan put everything into his sixth and final throw, hurling the hammer out to 51.93m. ‘When it all came down to my last throw, I knew I had to put everything into it and as it turned out I did. If I have any regret at all now, it is that I was not competing for Ireland on that day, he would say afterwards.

Following the games, Flanagan travelled to Ireland setting a new world record of 52.98m in the DMP Games at Ballsbridge. Flanagan’s final record came on 24 July 1909 at New Haven, Connecticut, when, at the age of 41 years and 196 days, he threw 56.19m. It made him the oldest world record breaker in the history of track and field.

Flanagan returned home to Limerick in 1911taking over the family farm following the death of his father in February1912. He continued to compete in Ireland winning hammer titles in both 1911 and 1912. His final international appearance was at the annual match against Scotland of 1911, held in Ballsbridge, where he won the hammer with a throw of 51.94m.

Following his retirement, he coached a number of athletes, including Patrick O'Callaghan, who took Olympic gold in the hammer at the 1928 and 1932 games. He died at home in Limerick, aged 70, on 3 June 1938. Matt McGrath paid tribute in the Amateur Athlete: ‘His skill and form was cultivated from early youth, and while I had an advantage of height and weight over him, still his form was more to perfection than mine.’

John Flanagan’s record:

Olympics:

1900, Paris, 1st, 51.01 m

1904, 1st, St Louis, 51.23 m

1908, 1st, London 51.93 m

14 world records between 1895 and 1901